Sagalassos Archaeological Research Project

Archaeologists excavating an early Roman imperial tomb in Turkey have uncovered evidence of unusual funerary practices. Instead of the typical method of being cremated on a funeral pyre and the remains relocated to a final resting place, these burnt remains had been left in place and covered in brick tiles and a layer of lime. Finally, several dozen bent and twisted nails, some with the heads pinched off, had been scattered around the burn site. The archaeologists suggest that this is evidence of magical thinking, specifically an attempt to prevent the deceased from rising from the grave to haunt the living, according to a recent paper published in the journal Antiquity.

Perhaps the best known examples of this kind of superstitious funerary practice are the so-called “vampire” burials that occasionally pop up at archaeological sites around the world. In the early 1990s, children playing in Connecticut stumbled upon the 19th-century remains of a middle-aged man identified only by the initials “JB55,” spelled out in brass tacks on his coffin. His skull and femurs were neatly arranged in the shape of a skull and crossbones, leading archaeologists to conclude that the man had been a suspected “vampire” by his community. They have since found a likely identification for JB55 and reconstructed what the man may have looked like.

In 2018, archaeologists discovered the skeleton of a 10-year-old child at an ancient Roman site in Italy with a rock carefully placed in its mouth. This suggests those who buried the child—who probably died of malaria during a deadly 5th-century outbreak—feared it might rise from the dead and spread the disease to those who survived. Locals are calling it the “Vampire of Lugnano.” And last year, archaeologists uncovered an unusual example of people using these tips in a 17th-century Polish cemetery near Bydgoszcz: a female skeleton buried with a sickle placed across her neck, as well as a padlock on the big toe of her left foot.

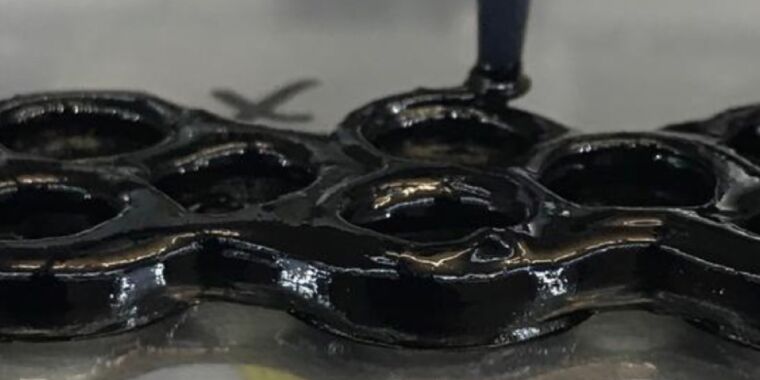

This latest find is part of a research project by KU Leuven in Belgium to excavate a specific area of the Sagalassos site in southwest Turkey. Humans occupied the region from the late 5th century BCE through the middle of the 13th century CE, despite significant damage from a 7th-century CE earthquake. The area in question is somewhat secluded and set off from the central and residential parts of the city. It consists of several contiguous terraces that came to be used for funerary purposes. The early Roman imperial tomb was first discovered in 1990, and archaeologists resumed work on the immediate surroundings in 2012, finding evidence of both burials and cremation spanning some six centuries.

Sagalassos Archaeological Research Project

The scattered nails were found at a roughly rectangular patch of burnt soil: the remains of a funeral pyre, complete with charcoal fragments of pine and scar, as well as burnt human bones. The burnt bones belonged to a single person, most likely a male who died around the age of 18, based on the osteological analysis. The bone fragments were still roughly anatomically arranged, with no evidence of handling them during or after the cremation.

Some of the charcoal remains appeared to be textiles, suggesting clothing or a shroud. There were also several artifacts found with the burnt remains: a coin dating from the 2nd century CE, a handful of ceramic vessels from the 1st century CE, two blown-glass urns, and an item made of worked bone with bronze hinges whose purpose is unknown. This is evidence that the mourners seemed to follow at least some of the traditional funeral rites.

It’s the 41 broken and bent nails—25 bent at a 90 degree angle with the heads pinched off, 16 bent and twisted but otherwise whole—recovered from the site that set this cremation apart. These were not coffin nails, which are usually found intact, and nails weren’t used in the construction of the funeral pyre. So the authors concluded that the broken nails had been deliberately scattered around the burial site to form a “magical barrier.” There are mentions in several ancient literary sources of nails being used to ward off diseases (Livy) or as a protection against nightmares (Pliny the Elder).