One of the ways we try to understand the origins of human intelligence is by looking at its equivalents elsewhere in the animal world. But that turns out to be more complicated than it might seem. Humans have a large package of behavioral traits that we lump together as intelligence, while many other creatures only have a limited subset of those traits. Some aspects of intelligence appear in species widely scattered across the evolutionary tree, ranging from cuttlefish to giraffes.

Even in animals with widely acknowledged intellectual capacities like birds, it can be difficult to understand whether evolution has directly shaped their intelligence or their smarts emerged as a side effect of something else that evolution selected for.

A study released today complicates the picture a little further. It does persuasively show that the ability to learn complex new songs is associated with problem-solving in a large range of bird species. But it also shows that other things we associate with intelligence, like associative learning, seem completely unrelated.

Testing everybody

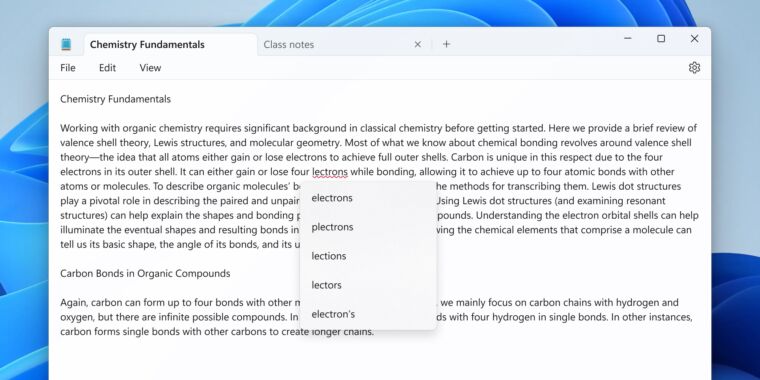

The paper, written by Jean-Nicolas Audet, Mélanie Couture, and Erich Jarvis of Rockefeller University, describes an evolutionary comparison of both song learning and a variety of tests of intelligence. The authors note that people have done this sort of analysis before, but only among members of the same species, and the results have often been contradictory. It’s possible, the team suggests, that’s simply because the variation among individuals isn’t large enough for an effect to be detected.

To get a diverse sample, the team went to a preserve a bit north of New York City and set up nets. As long as they captured at least a dozen males of a species (the ones who do the singing), they were included in the study. This was supplemented by a couple of captive species. Some of these, like the mourning dove, acted as non-learning controls. But the sample was heavily populated by songbirds like wrens and warblers. Among this sample, there are a variety of behaviors, like vocal learning, mimicry, and expanded song repertoires that could be used to classify their ability to engage in vocal learning.

After letting the birds go hungry overnight, the team gave them a chance to complete mental tests that provided food as a reward. Four of these tests involved manipulating obstacles of increasing complexity to get at the food. Another tested whether the birds could navigate around a transparent barrier to get at the food. And two tested associated learning, as birds were both given the chance to learn that a colored object was associated with food one day, and then had to unlearn that and learn a new association the following day.

With that data gathered, the researchers created scores for each species based on the performance of at least a dozen individuals. They then compared those scores with previously gathered information about their song abilities.

Smart singers

The results were a bit complicated. For starters, the species classified as open-ended learners—meaning they could incorporate new song motifs throughout their lives—were significantly better at problem-solving. These include species like cardinals, robins, and the goldfinch. Within this group, those with the largest repertoire of songs performed the best. But species that can mimic the calls of others, like the catbird and grackle, also scored above the mean. Close-ended learners, which can learn songs during a critical period when young, scored near the bottom of the list.

In contrast, there was no specific pattern on the other intelligence tests, which involved self-control and associative learning.

To test whether this effect was robust, the researchers repeated the analysis while eliminating different sub-groups, such as domesticated or non-learning birds. The association held up. Similarly, they performed principal component analysis on all the different measures of song learning complexity, and showed that this, too, was associated with problem-solving abilities. So, there seems to be a connection here.

Using data gathered by others, the researchers also found that open-ended learning species had larger brains relative to their bodies. But this relationship didn’t hold in species that mimicked the songs of others.

Complicating matters further, individuals from most species showed some variation in how they responded to tests. Distractions like the presence of a researcher or an unfamiliar object caused some individuals to perform poorly.

It’s complicated

One of the obvious messages here is that intelligence isn’t a single thing; it’s built up from a large variety of individual behavioral abilities. And because of that, we can’t expect that the evolutionary factors that drive the development of one aspect of intelligence apply to any of the others.

So, it’s possible that problem-solving is an accidental bonus from evolutionary selection for expanded song capabilities—singing, after all, is part of how these species ensure they produce the next generation. Once evolved, problem-solving can help provide access to more food, and so can end up the subject of selection itself. But none of this guarantees that any other aspect of intelligence will come to the fore.

All of this could help explain why some surprisingly sophisticated behaviors seem to be isolated in some species. But it doesn’t go very far toward explaining why such a large suite of things we term intelligence was present in our species.

Science, 2023. DOI: 10.1126/science.adh3428 (About DOIs).