Public domain

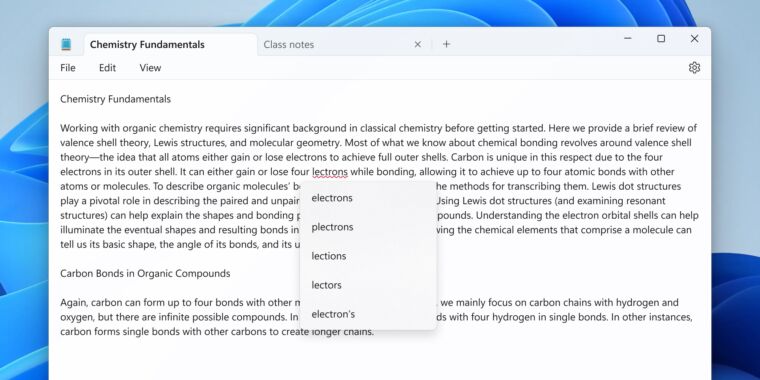

Around 1455, a medieval French painter and miniaturist named Jean Fouquet painted a small diptych with two panels, one of which depicts St. Stephen holding a strangely shaped stone—usually interpreted as a symbol of the saint’s martyrdom by stoning. A new analysis by researchers from Dartmouth University and the University of Cambridge has concluded that the stone depicted in the so-called Melun Diptych is most likely a prehistoric stone hand ax, according to a recent paper published in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal.

Originally housed in the Collegiate Church of Notre-Dame in Melun in northwest France, the diptych is painted in oil. The left panel depicts Etienne Chevalier, who served as treasurer to King Charles VII, clad in a crimson robe while kneeling in prayer. The figure to his right is St. Stephen, Chevalier’s patron saint, in dark blue robes, holding a book in his left hand with the mysterious jagged rock resting on it, while his right arm drapes across Chevalier’s shoulder. The right panel depicts the Madonna breastfeeding the Christ Child, possibly a portrait of the king’s mistress Agnes Sorel, or possibly the king’s wife Catherine Bude.

The two panels were once connected by a hinge, with a small medallion believed to be a mini-portrait of Fouquet as a kind of signature (he otherwise never signed his work). By 1775, the Collegiate Church was in dire need of funds for a restoration and sold the diptych, breaking it apart. The left panel is now housed at the Staatliche Museen in Berlin, while the right panel belongs to the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp, Belgium. As for the medallion, it’s now part of the Louvre’s collection in Paris.

The diptych remains fascinating to art historians to this day. Just last year, Monja Schünemann of Chemnitz University of Technology suggested that Fouquet painted the two panels so that folding them reveals a hidden image. She created a mirror image sketch of the left panel and superimposed it onto the right, essentially folding both panels together. The result was a new image in which Chevalier’s figure now appears to be kneeling within the folds of the Madonna’s cloak as if he is being nursed—sacred iconography known as a “lactatio,” per Schünemann. Past technological studies revealed that Fouquet had corrected the heads of both Chevalier and St. Stephen, in such a way as to ensure that certain points in the painted image would meet up in a specific way when the hinged diptych was closed.

Public domain

Co-author Steven Kangas, an art historian at Dartmouth, had long been fascinated by the jagged stone in the left panel because it looked like a prehistoric tool. When he met a couple of anthropologists at a seminar in 2021, they decided to collaborate to learn more about the object since its unique features did not seem random or invented entirely by Fouquet.

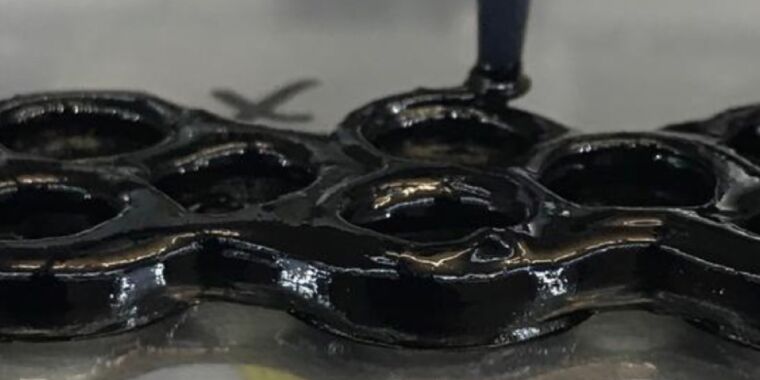

These Acheulean stone hand axes have been around for more than 1.6 million years and are a common archaeological find, although before the 17th century, they were not thought to be human-created objects, according to the authors. Rather, numerous recorded oral histories describe such objects as “thunderstones,” since it was believed they “shot from the clouds” whenever lightning struck the ground—although at least one 16th century German scholar, Georgius Agricola, dismissed that popular belief. Per Kangas et al., another 16th century scholar named Mercati noted a striking resemblance of thunderstones to arrowheads brought back from the Americas, but his observation wasn’t published until more than 100 years after the scholar’s death.