Mohamed Ismail Khaled

Over a century after a British archaeologist noted a blocked passageway in the ruins of Sahura’s Pyramid in Egypt and suggested it might lead to additional rooms, a team of Egyptian and German archaeologists have cleared out that passageway to prove the archaeologist right. They discovered several previously undocumented storage rooms and used 3D laser scanning to produce a map of the interior, shedding additional light on the structure’s architecture.

Sahura (“He who is close to Re“) was the second ruler of Egypt’s Fifth Dynasty and reigned for roughly 13 years in the early 25th century BCE. Egyptologists believe he was the son of the first Fifth Dynasty founder, Userkaf, and Queen Neferhetepes II. When the time came for Sahura to build his pyramid complex, he chose to do so at a site called Abusir instead of Saqqara or Giza, where prior pharaohs had constructed their edifices. Archaeologists have suggested this might have been because Userkaf had built a sun temple at Abusir. Regardless, Sahura started a new trend: Abusir became the main necropolis for three other pharaohs of the early Fifth Dynasty.

The decorative carved reliefs of Sahura’s Pyramid are widely considered to be unparalleled in Egyptian art, and the architectural design was a milestone in its use of palmiform columns, among other innovations; it became a template for subsequent pyramid/temple complexes in the Old Kingdom. The pyramid was smaller than the great monuments at Giza and Saqqara and more cheaply constructed, indicative of the decline in pyramid building in Egypt. For instance, the inner core was made of roughly hewn stones packed with a fill of limestone chips, pottery shards, and sand, held together with a thick clay mortar; only the outer casing was built with high-quality limestone. It might have made the pyramid faster and cheaper to build, but it also meant the pyramid deteriorated more over time.

The structure was largely reduced to rubble when the British archaeologist John Shae Perring first entered the burial chamber in 1836 after clearing the entrance to Sahura’s Pyramid and two others. He found fragments of a basalt sarcophagus and noted traces of a low passageway filled with debris that he believed led to additional rooms likely used for storage.

Mohamed Ismail Khaled

The ruined state of the structure discouraged others from exploring further until an Egyptologist named Ludwig Borchardt oversaw work to resurvey and excavate the pyramid and adjoining temples from 1902 to 1908. Restorations began in 1994 as the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities sought to open the Abusir necropolis to the public, reconstructing the causeway and uncovering limestone blocks decorated with elaborate reliefs previously buried under the sand.

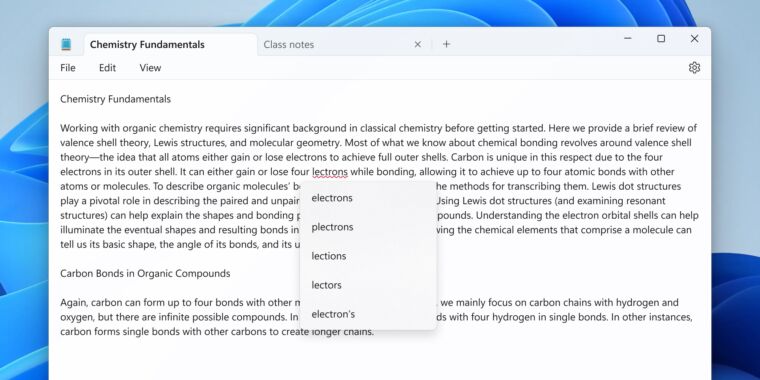

Egyptologist Mohamed Ismail Khaled of the Julius-Maximilians-Universität of Würzburg is the head of this latest conservation and restoration project, launched in 2019. In addition to cleaning the interior rooms, the team also worked to stabilize the pyramid to prevent further collapse. This included replacing the antechamber’s destroyed walls with new retaining walls and clearing away rubble, revealing the passage noted by Perring back in 1836. That in turn led to the discovery of eight storerooms, or “magazines,” possibly used to store funerary equipment.

“The discovery of the magazine area inside the pyramid of Sahura has completely changed our understanding of the architecture of pyramids in the Old Kingdom,” Khaled wrote. “Sahura might have been the pioneer of this architectural innovation which was adopted by his successors.” While the northern and southern parts are badly damaged, the archaeologists were pleased that the remains of the original walls and parts of the floor remained relatively intact. The team also used a portable lidar scanner to conduct detailed surveys of the pyramid for the permanent record.

Mohamed Ismail Khaled