Kim Jae-Hwan/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

North Korea launched a small military spy satellite Tuesday on the country’s first successful orbital launch since 2016. This, alone, would be newsworthy, but this launch comes with a twist.

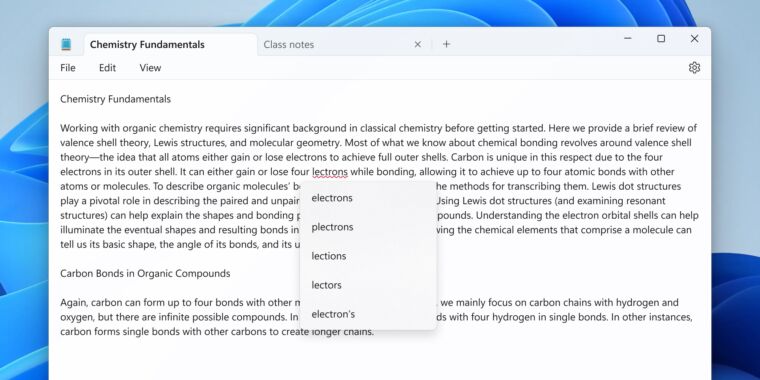

An automated camera operated by Yonsei University in Seoul, South Korea, captured the launch. The camera is part of a worldwide network of all-sky cameras to detect meteors streaking through Earth’s atmosphere. On Tuesday night, it caught a glimpse of North Korea’s Chŏllima 1 rocket climbing higher in the night sky until its booster engine cuts off. Then an upper stage engine fires to continue powering its payload into orbit, leaving behind the rocket’s spent expendable booster to fall into the Yellow Sea west of the Korean Peninsula.

Then, the night vision camera recorded a bright fireball. Instead of plunging into the sea, the booster explodes. It’s unusual to see a spent booster blow up during the launch of expendable rocket, so this raises questions. Did North Korea intentionally explode its rocket?

Falling into the enemy’s hands

The launch Tuesday was the third flight of North Korea’s Chŏllima 1 rocket, which appears to be more sophisticated than the launch vehicles North Korea used to deploy its first two successful satellites in 2012 and 2016. This rocket is likely based on North Korea’s newest intercontinental ballistic missile, the Hwasong 17, designed to deliver nuclear warheads to targets around the world.

With the addition of an upper stage, the design of which is unknown, the Hwasong 17 can be turned into a satellite launcher capable of hauling a payload of several hundred pounds into orbit. Intelligence officials in South Korea say the new missile and the Chŏllima 1 rocket may use engine technology North Korea acquired from Russia.

It’s also possible North Korea may have developed their own engines that appear similar to the Russian RD-250 engine, which consumes hydrazine in combination with nitrogen tetroxide. When those storable propellants come together, they automatically combust, making the engine design relatively simple and a good solution for a missile that needs to be on long-term alert.

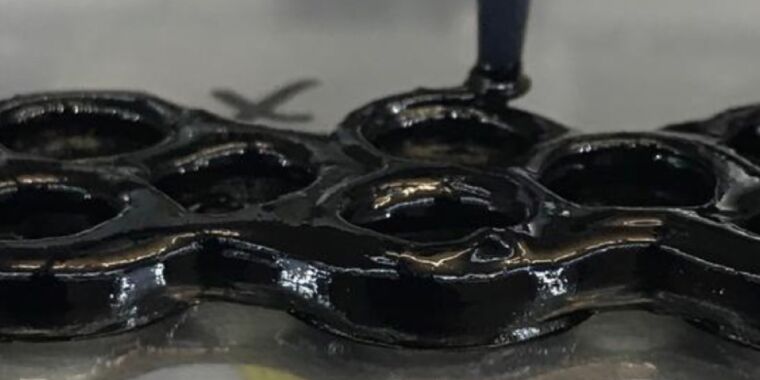

North Korea’s first two Chŏllima 1 launches in May and August ended in failure. After the May launch, South Korean officials said the country’s navy recovered relatively large fragments of the rocket from the Yellow Sea, along with wreckage of the satellite onboard the launcher. South Korea’s military said at the time that it would inspect the debris to determine whether foreign parts, such as Russian engine technology, were used on the rocket.

South Korean officials said the satellite had little military value, but leaders in Seoul haven’t said whether their inspections of the rocket revealed any new details about possible Russian involvement in the North Korean rocket program.

Nevertheless, Shin Won-sik, South Korea’s minister of national defense, pointed to warming relations between Russia and North Korea, including a meeting between Russian President Vladimir Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un at a Russian spaceport earlier this year. Kim and Putin discussed several areas of cooperation, including North Korean ammunition for Russia to use in its war in Ukraine, and Russian help on North Korea’s rocket program.

“Didn’t the first and second attempts fail because of engine problems? This time, the biggest feature is the success of the engine… It shows that Putin’s offer to help in August was not a pretense,” Shin said, according to Reuters. While there’s some debate among analysts and intelligence officials about the overall involvement of foreign countries in North Korea’s missile program, it doesn’t seem likely Russia could have supplied engines for Pyongyang to use on a rocket launch within less than three months.

South Korean Navy

It would make sense that North Korea would take the unusual step to rig its booster to explode before falling intact into the ocean, where South Korean vessels could recover the debris. That seems to be a likely explanation, according to analysts who track North Korea missile launch activity.

Marco Langbroek, a Dutch archeologist who expertly tracks missile launches on his website, concluded the booster explosion “could well have been deliberate” to keep the North Korean rocket from falling into the hands of South Korea.

The camera that recorded the North Korean launch was developed by Mike Hankey, an amateur astronomer and operations manager for the American Meteor Society, to observe naturally occurring meteors. They can also occasionally catch views of space debris and rocket launches, Hankey told Ars.

“The stations are designed to work together in a network to solve events and trajectories,” he wrote in an email to Ars. “We have about 200 worldwide. This is the first time we have recorded a North Korean launch. Also, the first time we have recorded a detonation.”

Yonsei University

The rest of the North Korean launch sequence appeared to go according to plan. The second stage of the Chŏllima 1 rocket continued into space, and a third stage then placed North Korea’s Malligyong 1 satellite into orbit.

North Korea’s state-run news agency declared the launch a success, and publicly available tracking data from the US military confirmed this. The military’s tracking radars detected the satellite in a polar orbit roughly 310 miles (500 kilometers) above Earth.

Images released by North Korea before the launch appeared to show the Malligyong 1 satellite is about the size of a refrigerator, larger than the satellites North Korea put into orbit before. The satellite is designed to take surveillance pictures of locations, presumably US and allied military forces, around the world. But it’s still too small to provide the highest-resolution reconnaissance imagery collected by spy satellites from the United States and other leading space-faring nations.

South Korea’s government condemned the North Korean launch Tuesday. Shin, South Korea’s defense minister, called the launch a “clear violation” of a UN Security Council resolution banning North Korean launches using ballistic missile technology. He said the launch was a “serious act of provocation” against South Korea and the international community.

In response to the satellite launch, South Korea said it will suspend parts of a 2018 military agreement with North Korea and resume reconnaissance of North Korean military forces in border areas.

Nov. 22, 2023: This story was updated with comments from Mike Hankey and details about Russian engine technology.