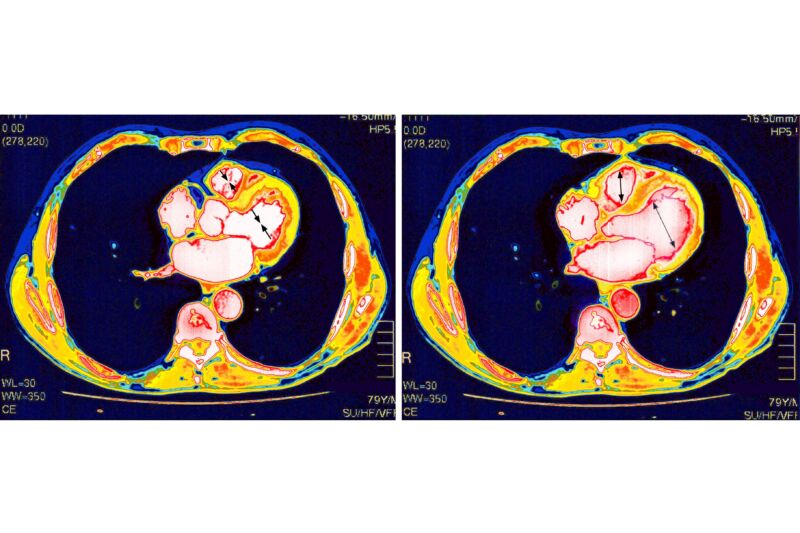

The mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines have proven remarkably safe and effective against the deadly pandemic. But, like all medical interventions, they have some risks. One is that a very small number of vaccinated people develop inflammation of and around their heart—conditions called myocarditis, pericarditis, or the combination of the two, myopericarditis. These side effects mostly strike males in their teens and early 20s, most often after a second vaccine dose. Luckily, the conditions are usually mild and resolve on their own.

With the rarity and mildness of these conditions, studies have concluded, and experts agree that the benefits of vaccination outweigh the risks—male teens and young adults should get vaccinated. In fact, they’re significantly more likely to develop myocarditis or pericarditis from a COVID-19 infection than from a COVID-19 vaccination. According to a large 2022 study led by researchers at Harvard University and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the group at highest risk of myocarditis and pericarditis after vaccination—males aged 12 to 17—saw 35.9 cases per 100,000 (0.0359 percent) after a second vaccine dose, while the rate was nearly double after a COVID-19 infection in the same age group, with 64.9 cases per 100,000 (0.0649 percent)

Still, the conditions are a bit of a puzzle. Why do a small few get this complication after vaccination? Why does it seem to solely affect the heart? How does the damage occur? And what does it all mean for the many other mRNA-based vaccines now being developed?

A new study in Science Immunology provides some fresh insight. The study, led by researchers at Yale University, took a deep dive into the immune responses among 23 people—mostly males and ranging in age from 13 to 21—who developed myocarditis and/or pericarditis after vaccination.

Probing possibilities

Since the rare phenomenon was first noted, immunologists and other experts have hypothesized that the vaccine could be spurring several aberrant immune responses that would explain the inflamed hearts, such as an autoimmune response or an allergic reaction. And the new study rules some of them out.

The researchers used blood samples from a subset of the patients to look at immune responses and compare them with those from matched vaccinated controls. They first compared antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and found no evidence of “overexuberant” or enhanced antibody responses against the virus that might explain the myocarditis and pericarditis. The anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody responses in the two groups were comparable, with the patients with the heart condition having comparable, if not slightly blunted, antibody responses.

The researchers next screened for auto-antibodies, that is, antibodies spurred by the vaccine that are misdirected against a person’s body rather than the virus. They used an established screening tool to scan for autoantibodies against over 6,000 human proteins and molecules. The researchers focused on over 500 of the probes that relate to cardiac tissue. They found no relative increase in the number of autoantibodies compared with the controls, suggesting that an autoimmune response was unlikely.

The researchers then took a broad, unbiased approach to compare the profiles of immune responses among the patients and controls. They found distinct immune signatures between the two groups, with patients showing elevated levels of immune signaling chemicals (cytokines) that are linked to acute, systemic inflammation. And those cytokines were accompanied by corresponding elevations in inflammatory cellular responses, particularly cytotoxic T cells. Further, the gene expression profiles of those T cells showed the potential to cause heart tissue damage.

Lingering questions

Taken together, the researchers concluded that the most likely explanation is that in these rare cases of myocarditis and pericarditis, the vaccine is spurring a generalized, vigorous inflammatory response that leads to heart tissue inflammation and damage.

“The immune systems of these individuals get a little too revved up and over-produce cytokine and cellular responses,” senior study author Carrie Lucas, professor of immunobiology at Yale, said in a statement.

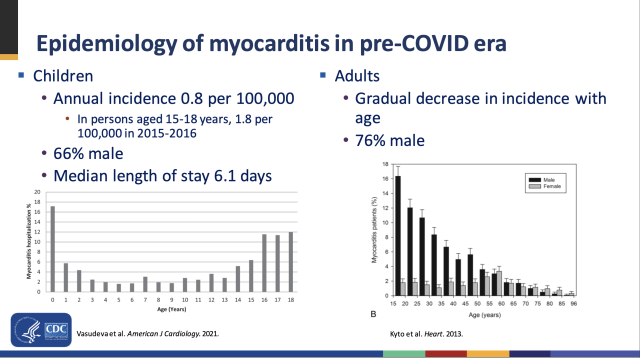

While the study offers a possible answer to the “how,” it doesn’t answer all the questions—including some of the whys, such as why young males? And why the heart? The researchers note that young males, particularly in their late teens, are the most common group to develop myocarditis generally, from any cause. Medical experts don’t know why this is the case, but have hypothesized that it is down to a blend of environmental, genetic, and hormones, particularly testosterone. As for why the heart seems to be uniquely damaged, co-author Akiko Iwasaki, also a professor of immunobiology at Yale, speculated that it could be because the heart is constantly working and has limited potential for tissue regeneration, making it more susceptible to inflammation.

Lastly, it remains unclear what exactly in the vaccine is igniting the boosted inflammatory response—the lipid nanoparticles in the vaccines that carry SARS-CoV-2 mRNA or the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA itself. Preliminary evidence suggests both components can spark inflammatory responses on their own. The authors hypothesize the two components may be working together to produce the exaggerated response, but researchers will need more data and research to understand this and further optimize the safety profile of the vaccines.

For now, the finding that an inflammatory response is behind the cases can help guide treatment and prevention. A Canadian study from last year suggested that extending the interval between mRNA vaccine doses can reduce the chances of myocarditis and pericarditis in young males. But, the new study may bring some relief when it does occur—self-resolving inflammation is less concerning than a difficult-to-treat autoimmune response.