In 2007, when phones began changing,

My mother engaged in some life rearranging.

A client of hers used some “herbal” pomade,

Then he itched and he burned and he swore and he swayed.

His hair all fell out and it hurt when he sat,

He was owed, he complained, compensation for that.

My mother agreed, and it came out at trial:

The “herb” in the cream was your basic yak bile,

Well known for its harm to follicular lining

But cheap when you needed to keep male hair shining.

So mom won her case ‘gainst the maker of hair gel,

And got a promotion and started to buy. Well—

She bought a red car, a blue dress, and a Shih Tzu

With money that being made partner will get you.

She purchased a lake house, a boat, and two skis,

Booked space on a flight known for pulling 6 Gs,

She joined Junior League and a gym called “The FitZone”

But bigger change came when she snapped up that iPhone.

Watching Steve Jobs in his black shirt and jeans

As he pitched the rectangular slab of her dreams,

She saw in his spiel the last item she needed,

to keep her life’s lawn well-cut, watered, and weeded,

The one thing she lacked that would make her complete:

A phone that would mark her among the elite.

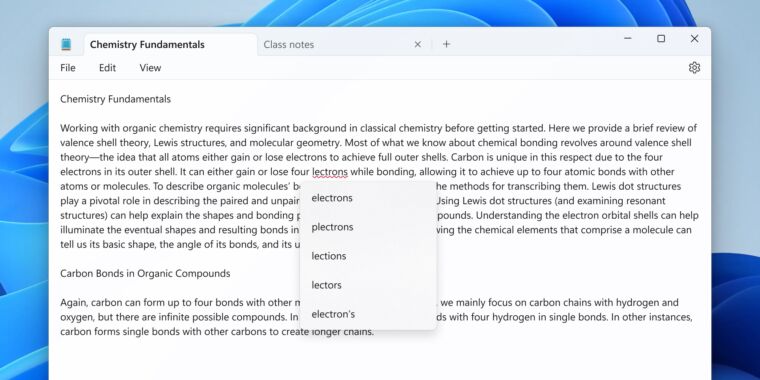

She used it for voice calls, text messages, maps,

And—when Jobs allowed it—then even for apps.

At first she took pleasure in whipping it out,

But soon she had questions; later came doubt.

Moving through life needed motion and sass,

But here she was now, just swiping on glass.

On subways, in cars, while at church, in the bar,

She stuck to that phone like one mired in tar,

Unable to extricate finger or eye,

Caught like a mammoth just waiting to die.

The things in her life that were golden and green

Soon looked beige and boring set next to that screen.

My dad was a “writer”—I put that in quotes,

Since he never wrote anything longer than notes,

That went in my lunchbox or in my mom’s purse;

When we left the house, he just stayed in and cursed.

Writer’s block had long blocked him from living his genius,

A bona fide, certified, true act of meanness

Doled out by a cosmos so fickle and foul

That it blessed dad with bricks but provided no trowel.

He cooked all our meals, cleaned our clothes, skimmed our pool

Wore green sneakers, red glasses, and had a strict rule

Against washing his jeans—said it messed with the denim—

But under the cool lay a thin streak of venom.

So mom went to work and she brought home the bacon,

While dad stayed inside on a long-term vacation.

A self-proclaimed “genius” who’s blocked might start drinking,

When hopes and raw talent both feel like they’re sinking

But rather than going the Hemingway route,

Dad scooped up the bottles and threw them all out.

He holed up instead in the den with a TV,

A seventy-five inch reflective monstrosity,

Loudly proclaiming to any who’d listen

That prestige TV’s “golden age” had arisen.

He hatched a keen plan to watch every minute

Of every long series with “real actors” in it.

Forget those new novels, forget those old poems,

And don’t even mention the biblical tomes.

Hollywood offered the realest life lessons:

The Ts and the As and the Smiths and the Wessons;

Hearts on parade; life’s jocularity;

drugs sold in Baltimore; peace, love, and charity.

But—

Whenever I happened to peek in the door

He seemed to be lying asleep on the floor,

Reality shows were binge-blasting above him,

Great British bakers with great British muffins.

The “truth” TV showed him was older than dirt:

Spend your life lying down and your soul starts to hurt.

If they were both addicts, I remained clean;

Life still had a sheen that out-shined any screen.

I read and I built and I played—then repeated,

While they binge-watched Frasier or read what they’d tweeted.

But one bright blue day, I could take it no more,

A dim indoor life was both safe and a bore.

So I put down my book and I rose from the couch,

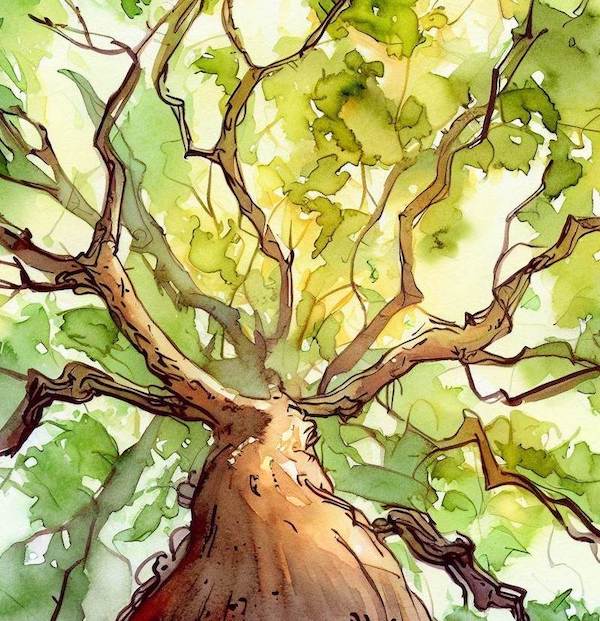

Went outside, climbed a tree, slipped right down and screamed “ouch,”

Since I broke half the bones in my left and right feet

And for weeks couldn’t walk, though I could learn to beat

A huge backlog of games for my sweet new PlayStation,

Brought up to my room by a dark delegation:

Two guilty-eyed parents, both clearly aware

The outdoors wasn’t “great,” no one needed “fresh air,”

And “go out and play” was a scam by some nurses

Who’d push us outside… and then right into hearses.

We were safer at home, in the bedroom or basement,

Enthralled with a screen—the best cheap risk abatement.

My parents retreated, their offering made

And I stayed in bed, where I slept and I played.

No timers, no limits, no digital locks

And no one complained if I wore the same socks

For five days in a row while I wandered the West

Where I gambled, shot, looted as one of the best

Of the worst men on earth, who would take all your cash

And then rustle your horses—until a game crash

Corrupted each one of my character saves

And my undying bandit now rests in his grave.

I role-played my way through space outpost and ocean,

Kissed girls, then a guy, then two alien Krogan

And after I saved Ancient Greece, modern Gotham,

The Milky Way, Earth, and a meadow in blossom

I jumped into war games and called down some woe

Upon trench-coated Nazis, last hateable foe.

Then I found out, when my six weeks were through,

And the casts were sawed off and my feet felt like new,

That the “real world” was scary and not as much fun

As a good online game, tight controls, and a gun.

The universe spoke to us each that December

In ways that no one would much want to remember.

My dad had become the first human to view

Each glorious show in his long Netflix queue.

A powerful sense of despair then descended

As he pondered the paths in which his life had tended.

Without the TV, he had no good distraction

From thinking and thinking about his inaction.

And mom gained a habit of checking her phone

At inopportune times—not just when alone.

Once in the courtroom, she gave a small snort

After reading a joke text on spousal support.

The judge made her stand and then read her a lecture,

Suggesting that maybe her friends shouldn’t text her

While she was in court or there’d be an attempt

To blackball my mom and find her in contempt.

I spent so much time slaying demons and liches

I gained thirteen pounds and came down with eye twitches

Which didn’t concern me until Christmas came—

And I spent it upstairs with a video game.

Something wasn’t quite right—life was losing its savor

That hard-to-define-it-but-you’ll-know-it flavor.

All three of us sat on our beds or on chairs

Feeling much too depressed to go up or down stairs.

In the New Year, my mom called a Zoom meeting

And we all said yes, that we should start treating

Our addictive and yet unacknowledged submission—

And start seeing screens with a lot more suspicion.

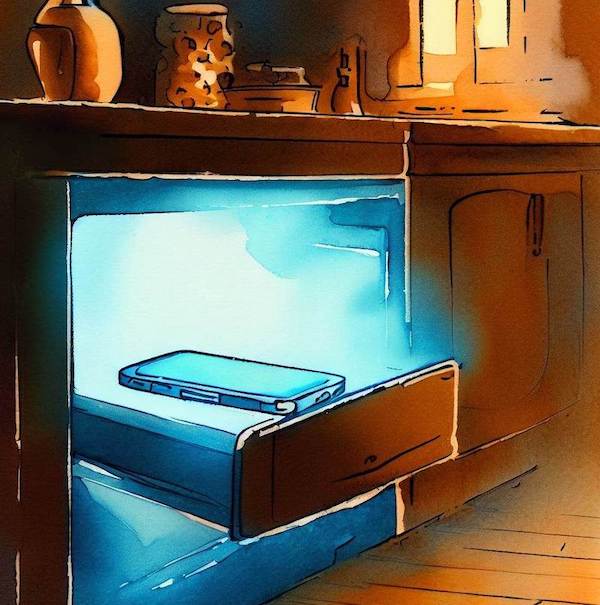

So this would be it: our year of detoxing.

We took all our screens and spent Sunday night boxing

Them up and then down to the basement we went;

We were going to be free—one hundred per cent.

“We’ll rethink it all,” my dad said, “Like Descartes!

And rebuild our lives from the floor to rampart.”

Then came the fidgets, the phantom limb feeling

That some part of you was cut off and not healing,

That reflex of reaching for phone or controller

And finding your hand felt a little bit colder

With nothing to cradle, no glorious gizmos

That promise to stop you from thinking of escrows,

Of egos, of toads beneath harrows, of death

That still stalks us with rattling breath…

Well—

We tried what we could, we ate family dinners

And read books on how to think just like real winners,

Books written by not-yet-disgraced CEOs

And relationship gurus who maintained their pose

That life had a code, and they had it figured;

Everything came down to slogans and zingers.

“Self-love is not selfish,” my mother would say,

Walking past with her yoga mat. “So—Namaste!”

My dad ditched his flannels for logoed T-shirts

That said things like “Good Vibes” and “Selfishness Hurts.”

But I couldn’t quit the allure of distraction—

Did we have to kill all of that sweet screen time action?

Could ten minutes matter—heck, round up to an hour—

With that glowing blue screen of unusual power?

So on Easter Sunday, screens still in the basement,

I crept out at night from my hidden emplacement

Yearning to feel that now long-lost connection,

Looking to have a device resurrection.

I tip-toed downstairs, where I flipped on the switch

And startled my dad, who said, “Son of a bitch!”

Because there were my parents, on a ratty old loveseat

With gadgets plugged in and a cheese plate to eat.

They sat side-by-side, I saw with a shock,

she texting away while he watched The Rock.

Self-help hadn’t helped, so our loins then we girt

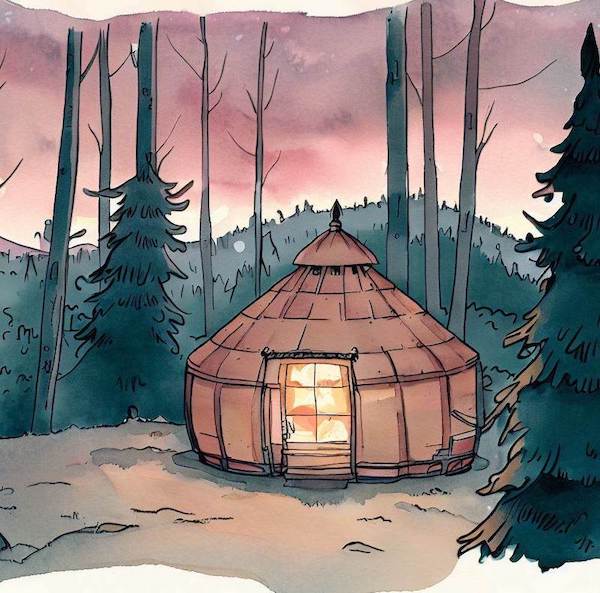

For a nine-hour drive to New York—and a yurt.

The Shambala Center would unchain our brains

Through mindfulness, yoga, and chanted refrains.

(And some really remarkably boring-ass food;

Brown rice will sustain you but won’t lift your mood.)

It was Buddhist by way of San Fran and Cape Cod;

Big dollops of Burning Man, self-help, and God.

We woke up at six and imagined hot showers

While hiking instead through the cold for two hours.

We warmed up by milking five cows and six goats,

Then shoveling muesli bars into our throats.

Meditation time followed, from nine until ten,

At which point we down-dogged—then got Zenned again.

We lived in each moment, just present and grounded

Content without screens until mealtime bells sounded.

Post-lunch you could meet with a life coach of sorts

Who wore sandals and socks and some shocking short shorts

She held herself out as a spiritual leader,

A wonderfully wise counselor and soul reader.

Mom, dad, and I got the same strong advice:

“Treat your cell phones like vermin; treat them like lice!

Shampoo them and tweeze them right out of your life,

And if that doesn’t work—go ahead, grab a knife!

Cut them and stab them until they’re all dead;

No gadgets should come anywhere near your head.”

This felt extreme, but she was persuasive;

“Doing without” came to seem innovative.

But she closed each session with one final koan:

“Bury your fears before ditching your phone.”

Feeling better and kinder and somewhat more mellow,

Without all those gadgets to thunder and bellow

Their notifications, their beeps and their boops,

Our brains settled down and stopped spinning in loops.

But three weeks in tents being mindful as balls

Made us realize how much we loved houses and walls.

Back home we headed, not “cured” and not “better,”

But willing to hack at our digital fetter.

Dad gave up his plans to watch all the way through

The Lord of the Rings and the whole MCU,

And instead moved his TV right out of the den,

Then stopped, picked it up, put it back in again.

“I don’t need an office,” he said, “and the desk?

You can forget it—just so Kafkaesque.

My new way of writing is outdoors and rambling.

Treat life like a slot machine and then get to gambling

That words won by walking will mean something special—

Real and alive, not just self-referential.”

No more skinny jeans, no more sweatshirts with hoods.

In khakis and boots, Dad went tramping through woods.

He got poison ivy his second week out,

But wasn’t distracted by even this bout

Of bad fortune, nor by the deep itching

From gnats that in week four invaded his stitching.

He owned a hard truth that was clear to us all:

Dad wasn’t a Jesus nor even Saint Paul.

He was (at the most) a quite minor apostle

Making his way through the throng and the jostle

Of life with good grace and a few observations

Jotted while fleeing those indoor temptations.

He bowed to his failures as though to a teacher,

Which unblocked the words, even when they were weaker

Than he might have wanted—than he might have yearned for—

And yet he was working and up off the floor.

My mother faced down her imposter syndrome

And read up on healing her microbiome.

She downed probiotics but felt like a jerk

When repeating her mantra: “I’m good at my work!”

But as she grew comfortable with her own worth

She gradually felt like her one shot on earth

Was wasted on suing the modestly vile—

Like those who made cash selling rare black yak bile.

Yes, bile was bad but not quite as soul killing

As finding yourself socialized into willing

That you could spend more of your life’s precious powers

Contractually parsing for billable hours.

Who needed a Bentley or rides on a jet

When all that one wanted—all one could get—

In an ultimate sense was some love and affection

(And a quite passable strappy sandal collection.)

But when she had shared this enlightened perspective

With her fellow partners, she got a corrective

To her big idea that less work wasn’t lazy.

The partners just looked at her like she was crazy,

A “typical woman” who valued her kid

More than flying first class on Spring Break to Madrid.

So Mom quit. She walked out. She began something new,

A firm where the goal was not just to accrue

But to live. Sure, money was less by a factor of two,

Yet so was the time—“And you can’t beat the view

From your own corner office,” she said with a smile,

“Even when it looks out on the city trash pile.”

Having worked on herself and then taken real action

Mom now needed less of that online distraction.

She used her phone daily but once through our door,

The glowing rectangle went into a drawer.

As for me, I could spin out a credible story

About how I came to stop playing those gory

And glorious shooters I loved to lose days in,

But that would not be a true-hearted confession.

Games are amazing! You can’t just say no

To a drug that’s so potent, it lets you go pro

And play e-sports tourneys for serious bank

By attacking with Ryu or driving a tank.

So I couldn’t stop gaming—perhaps I had failed,

But my custom controller just couldn’t be jailed.

Yet I did venture out with my mom and my dad

On short winter walks that were quiet and sad

And long summer rambles that filled me joy

In green growing things and the ways they destroy

That terminal sense of a distance from life,

Our love of distraction, “the news,” and of strife

And offer instead a rest from algorithms,

Not free from our problems—but slowed to life’s rhythms.

And though I kept thinking of games in 3D,

I ignored all my fears and then free-climbed a tree.

So that’s the whole story, with jolts and collapses

And more than a few temporary relapses,

Of how screens invaded, like all colonizers,

Dismissing our cultures, proclaiming theirs wiser.

And much of it was unbelievably awesome

But some was just petty, and parts were just dumb.

Amazing the way screens could melt down like wax

And fill in our minds’ and our hearts’ biggest cracks,

To keep us engaged with the unending new

While ignoring the quiet, the boring, the true.