Marcin Wichary

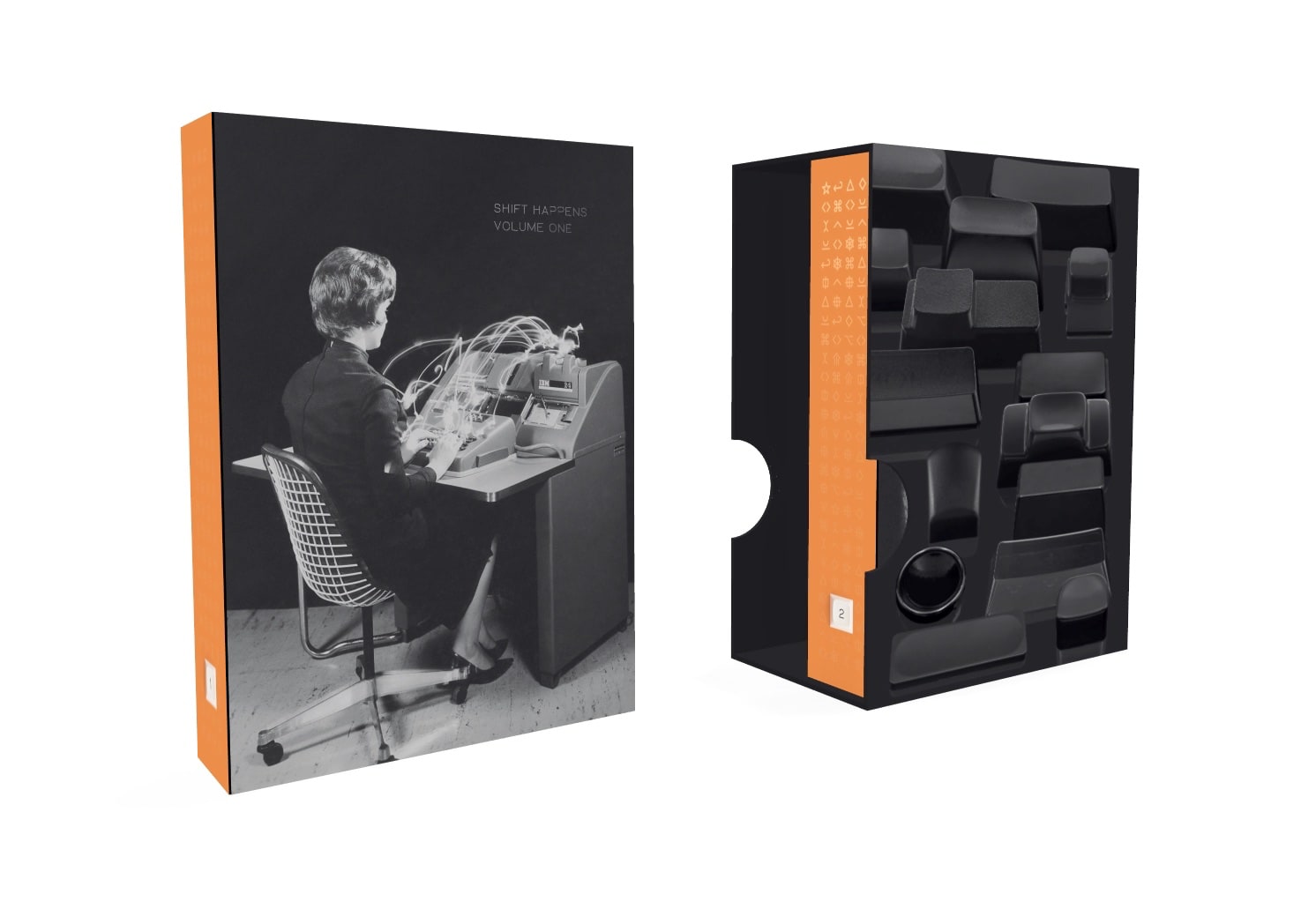

It’s the 150th anniversary of the QWERTY keyboard, and Marcin Wichary has put together the kind of history and celebration this totemic object deserves. Shift Happens is a two-volume, 1,200-plus-page work with more than 1,300 photos, researched over seven years and cast lovingly into type and photo spreads that befit the subject.

You can preorder it now, and orders before October 4 (Wednesday) can still be shipped before Christmas, while orders on October 5 or later will have to wait until December or January. Preorders locked in before Wednesday also get a 160-page “volume of extras.”

Wichary, a designer, engineer, and writer who has worked at Google, Medium, and Figma, has been working in public to get people excited about type, fonts, and text design for some time now. He told the Twitter world about his visit to an obscure, magical Spanish typewriter museum in 2016. He put a lot of work into crafting the link underlines at Medium and explaining font fallbacks at Figma. Shift Happens reads and looks like Wichary’s chance to tell the bigger story around all the little things that fascinate him and to lock into history all the strange little stories he loves.

He also did 40 interviews, made two custom fonts, wrote 5,000 lines of InDesign automation code, and uploaded 350 books and articles from his research to the Internet Archive.

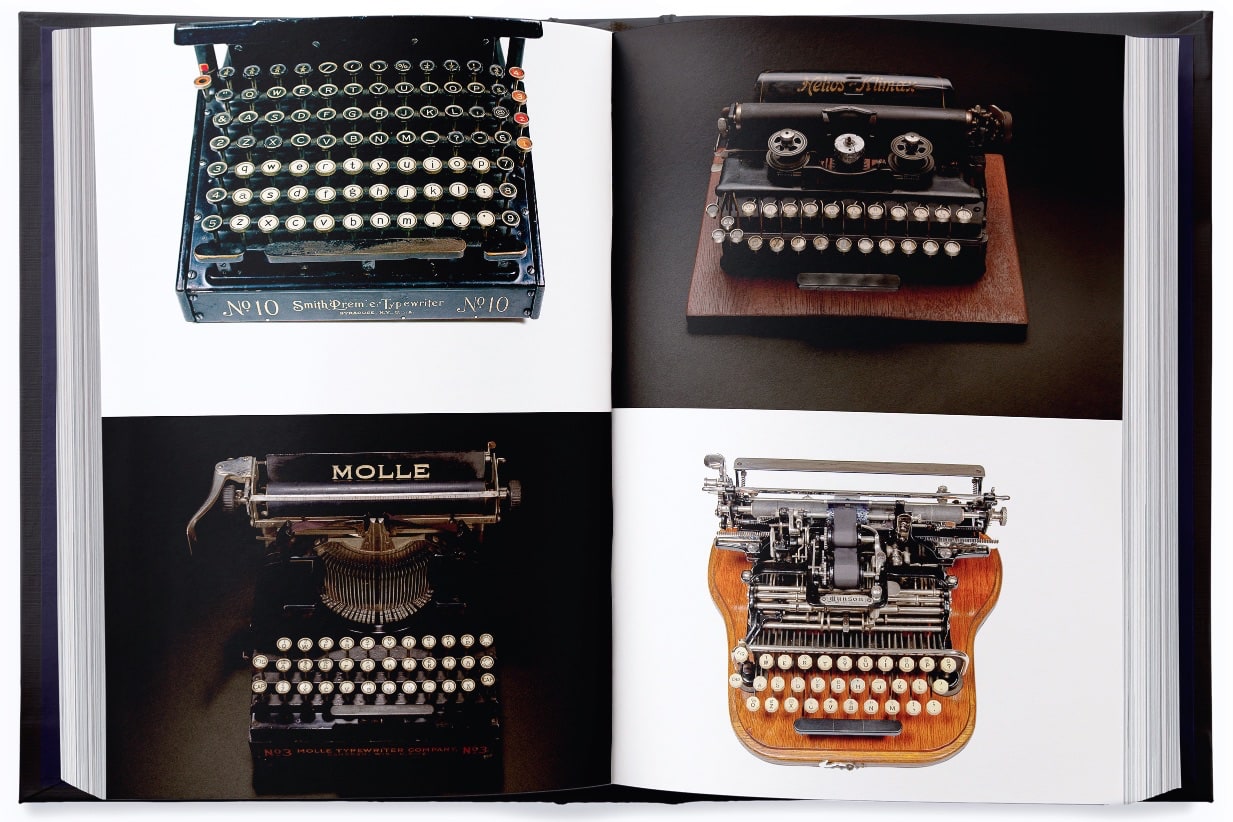

Wichary answered a few of our questions about Shift Happens, particularly one chapter on the “Shift Wars,” when typewriter companies entered fierce competition—with press-announced typist showdowns—to prove which layout was more efficient: keyboards with separate keys for upper-case, lower-case, and every other character, or keys which physically shifted their type mechanism to switch between them. The reasons shifting won out are not quite as obvious as they might seem.

A rendering of Shift Happens, with Volume 1 removed from its custom slipcase.

Ars: Your book sets out to connect the realms of ink/type-based machines and computers. Have those two realms been researched and written about separately all this time? Why do you think that is?

There have been a bunch of interesting books about typewriters—some appearing as early as the 19th century—but indeed nothing that extended from that into the world of computers and mechanical keyboards today.

I’m curious why myself! It’s possible that the scope was too daunting or that before the recent resurgence of mechanical keyboards it didn’t seem like it would be a subject of interest to anyone? But also, in 2016, Matthew Kirschenbaum published a great book about the history of word processors that connected both of these worlds on one specific axis, and reading that at the same time I was doing early research made me so excited. It seemed like keyboards were a space of so many fascinating, almost fractal stories, that they could support not one more but many more books.

Marcin Wichary

Ars: What kind of work was required to set all the specialty footnote glyphs and key characters into the text? (Meta note: I would be tremendously intimidated to try to lay out a book that would be read by type enthusiasts).

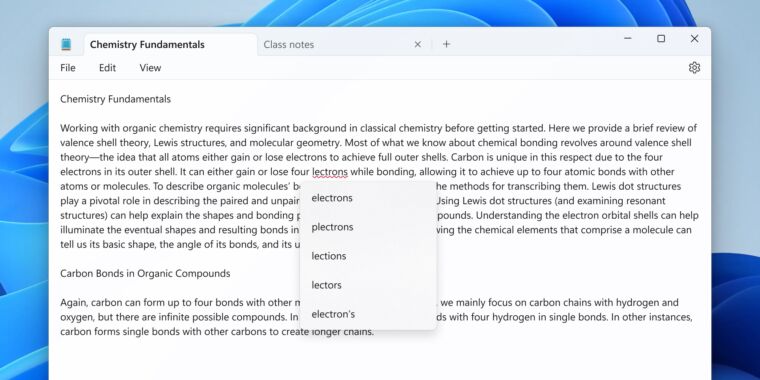

I am a web guy, and I used to think that the web (just like typewriters, once) took away a lot of hard-won typesetting nuance and tradition. But it turns out that the web also makes it much easier to do certain things. To have a word be surrounded by a rounded rectangle—a visual representation of a key—is a few lines of CSS or a few clicks in Figma. But for the book, I had to cut my own font and then write Python scripts to do typesetting inside the font-making software, which I’m pretty sure you are not supposed to do?

Similarly, I wrote a lot of long scripts to have the footnotes do exactly what I wanted. That’s the beauty and also a curse of being a once-in-a-while programmer: Instead of accepting the footnote limitations in common software, I could imagine writing something better, but at that point, I also had to start from scratch and own the entirety of my messy footnote-placing engine. And it turns out, writing typesetting engines is really, really hard.

As for footnote glyphs… I had a lot of fun finding keyboard symbols throughout history and repurposing them here. In this and a few other ways, I wanted to keep the book lightweight and fun. There are tons of little moments, Easter eggs, and even an intentional typo or two.

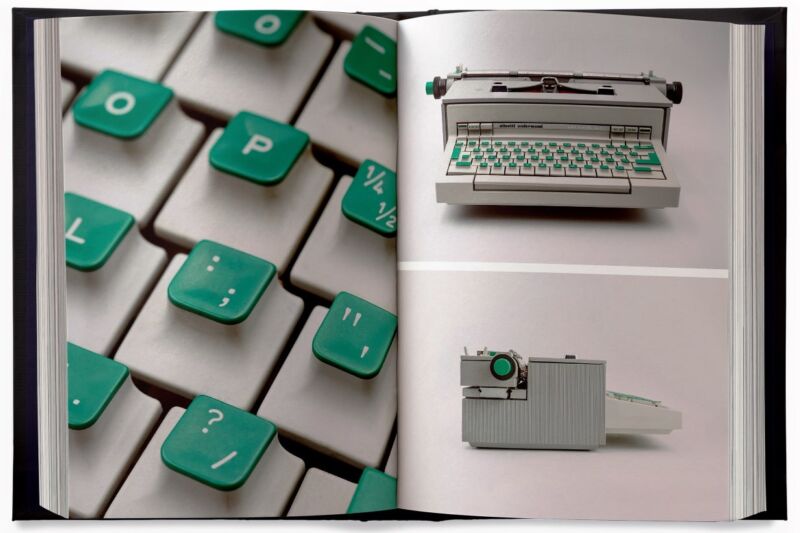

Photo spread from the chapter “Shift Wars” in Shift Happens. Clockwise from top left: Smith Premier No. 10 (dual keyboard), Helios Klimax (three shifts, two rows), Munson (two shifts), Molle (two shifts and ortholinear layout).

Marcin Wichary