Gentoo penguins are the world’s fastest swimming birds, clocking in at maximum underwater speeds of up to 36 km/h (about 22 mph). That’s because their wings have evolved into flippers ideal for moving through water (albeit pretty much useless for flying in the air). Physicists have now used computational modeling of the hydrodynamics of penguin wings to glean additional insight into the forces and flows that those wings create underwater. They concluded that the penguin’s ability to change the angle of its wings while swimming is the most important variable for generating thrust, according to a recent paper published in the journal Physics of Fluids.

“Penguins’ superior swimming ability to start/brake, accelerate/decelerate, and turn swiftly is due to their freely waving wings,” said co-author Prasert Prapamonthon of King Mongkut‘s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang in Bangkok, Thailand. “They allow penguins to propel and maneuver in the water and maintain balance on land. Our research team is always curious about sophisticated creatures in nature that would be beneficial to mankind.”

Scientists have long been interested in the study of aquatic animals. Such research could lead to new designs that reduce drag on aircraft or helicopters. Or it can help build more efficient bio-inspired robots for exploring and monitoring underwater environments—such as RoboKrill, a small, one-legged, 3D-printed robot designed to mimic the leg movement of krill so it can move smoothly in underwater environments.

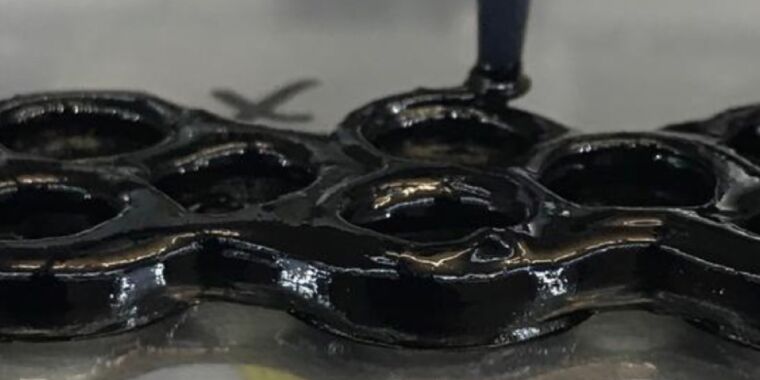

Aquatic species have evolved in different ways to optimize their efficiency while moving through water. For instance, mako sharks can swim as fast as 70 to 80 mph, earning them the moniker “cheetahs of the ocean.” In 2019, scientists showed that one major factor in how mako sharks are able to move so fast is the unique structure of their skin. They have tiny translucent scales, roughly 0.2 millimeters in size, called “denticles” all over the body, especially concentrated in the animal’s flanks and fins. The scales are much more flexible in those areas compared to other regions like the nose.

That has a profound effect on the degree of pressure drag the mako shark encounters as it swims. Pressure drag results from flow separation around an object, like an aircraft or the body of a mako shark as it moves through water. It’s what happens when the fluid flow separates from the surface of an object, forming eddies and vortices that impede the object’s movement. The denticles in shark skin can flex at angles more than 40 degrees from its body—but only in the direction of reversing flow (i.e., from tail to nose). This controls the degree of flow separation, similar to the dimples on a golf ball. The dimpling, or scales in the case of the mako shark, help maintain attached flow around the body, reducing the size of the wake.

Marsh grass shrimp maximize forward thrust thanks to the stiffness and increased surface area of its leg. They also have two drag-reducing mechanisms: The legs are about twice as flexible during the recovery stroke and bend heavily, resulting in less direct interaction with the water and a reduced wake (smaller vortices); and rather than three legs moving separately, their legs essentially move as one, significantly reducing drag.

There have also been numerous studies examining the biomechanics, kinematics, and fin shape of penguins, among other factors. Prapamonthon et al. specifically wanted to delve deeper into the hydrodynamics of how the flapping wing generates forward thrust. According to the authors, aquatic animals typically employ two primary mechanisms for generating thrust in the water. One is based on drag, like rowing, and well suited for moving at lower speeds. For higher speeds, they employ a lift-based mechanism, flapping, which has been shown to be more efficient at generating propulsion.