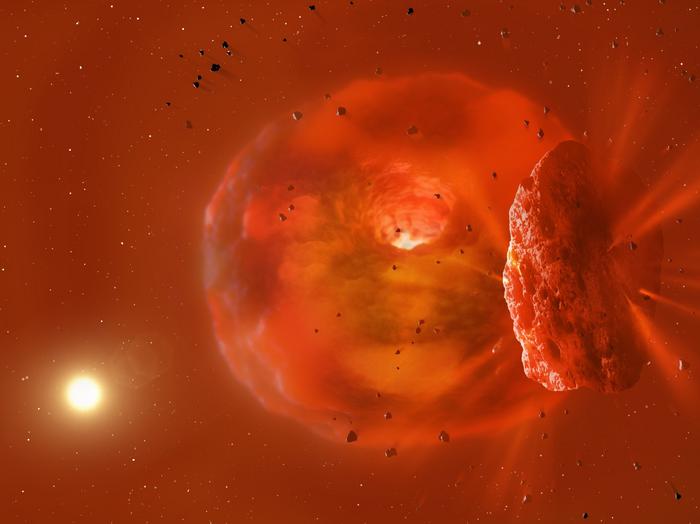

Planet formation is thought to be a messy process, as lots of growing planets end up in unstable orbits, resulting in large collisions like the one that resulted in the Moon’s formation. The messiness may not end there, as many exosolar systems have indications that their planets migrated after their formation, creating the potential for further collisions. Again, there are indications that a similar thing happened in our own Solar System, as Jupiter and Saturn seem to have moved around before reaching their present orbits.

All the evidence for these collisions, however, is indirect or the product of modeling. Planetary migrations are too slow for us to track them, and we can’t image planets that are close enough to their stars for collisions to be likely.

But a large team of scientists now think they have evidence of a smash-up of giant planets orbiting a Sun-like star. The evidence comes from a combination of two unusual events: the sudden brightening of the star at infrared wavelengths, followed over two years later by its dimming in the visual.

On and off

The star at issue, originally given the catchy name 2MASS J08152329-3859234, is distant and Sun-like, and even the authors of the new paper describe it as having been “otherwise unexceptional.” (It was also known by the equally catchy Gaia DR3 5539970601632026752.) That changed in December 2021 when it was picked up by a program that identifies new supernovae by looking for sudden changes in the intensity of stars. The All Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae noticed that it had dimmed dramatically and gave it yet another name, ASASSN-21qj. We’ll be using that one since it’s by far the most concise option.

Dimming like that seen in ASASSN-21qj is unusual, but not unheard of—the past few years have seen astronomers excited by the sudden dimming of Betelgeuse, a nearby massive star. That event was eventually ascribed to a large cloud of dust, and similar explanations were offered for ASASSN-21qj by a paper published earlier this year. And large clouds of dust aren’t so uncommon that they’re exceptional.

But the team behind the new work, which was studying ASASSN-21qj as well, chanced upon something that did make it exceptional. They looked for images of the star that predated its sudden dimming and obtained some taken by NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer. These showed that, about two and a half years before the dimming of ASASSN-21qj at optical wavelengths, it experienced a sudden brightening in the infrared. And that brightening lasted long enough that it was still going when the dimming event started.

Either of these events on their own is quite unusual. The fact that they both occurred to the same star would be extremely improbable, suggesting that the two events are likely to be connected. “Such a notable combination of observations,” the team writes, “particularly the 2.5-year delay between the infrared and optical variation, requires an explanation.”